Designing the Fragmenting Component

This page records the high-level design decisions which went into Chemist’s Fragmenting component.

What is the Fragmenting Component?

Most computational chemistry energy methods compute the energy of a target chemical system. Some methods do this by breaking the target chemical system into pieces. Each piece, or “fragment” is meant to simulate a subset of the target system (the target system is often called the “supersystem” to emphasize the sub-/super-set relationship of the two). Chemist’s Fragmenting component is charged with providing classes for representing fragments.

Why Do We Need a Fragmenting Component?

In addition to fragment-based methods, i.e., methods which approximate the target system’s properties via the (generalized) many-body expansion, methods such as QM/MM and ONIOM also rely on sub-/super-set relationships. We thus will have a need to represent these sub-/super-set relationships in the inputs/outputs to algorithms. The fragmenting component is charged with providing the user with the classes needed to express these relationships.

For many people the next question may be “why do we need a whole component for

this vs. say just using std::vector<Molecule> objects?” The answer is

performance. Particularly for large supersystems the number of subsets can be

very large (n.b., the number of terms in the full MBE grows

exponentially in the number of subsets). Storing all of those subsets as

individual objects requires a large amount of memory and leads to inefficient

operations, e.g., using Molecule::operator== will compare the full state,

but since the subsets contain atoms from the same superset, we can get by with

determining if say atom 1 is in both sets. Ultimately, as described in the

next section, the fragmenting component will need to parallel the chemical

system component (and potentially other Chemist components) and we have thus

opted to decuple fragmenting from the component(s) being fragmented.

Fragmenting Considerations

- chemical system class

Most fragments stem from decomposing a chemical system. In Chemist, chemical systems are modeled by the

ChemicalSystemclass and thus fragments should be defined with respect to aChemicalSystemobject.As a corollary, we also want fragments of a

ChemicalSystemto be usable whereverChemicalSystemobjects are used.

- chemical system hierarchy

The

ChemicalSystemclass is actually a hierarchy of classes. Conceptually the easiest way to fragment aChemicalSystemobject is to fragment it piece-by-piece, i.e., we expect users to first fragment theNucleiwithin theChemicalSystem, then assign electrons to thoseNucleiobjects to makeMoleculeobjects, and then assign external fields to theMoleculeobjects to createChemicalSystemobjects.Similar to chemical system class we want fragments of

NucleiandMoleculeobjects to be usable whereverNucleiandMoleculeobjects are usable.

- caps

When the supersystem contains large covalently-bonded molecules, fragments will usually severe covalent bonds. One of the most common strategies for dealing with this is to “cap” the broken bond with a monovalent atom (or sometimes set of atoms).

When a fragment is passed to an algorithm meant for a traditional

Nuclei,Molecule, orChemicalSystemwhich elements come from caps and which come from the supersystem is irrelevant; however, this changes for algorithms needing to assemble the resulting properties.

- non-disjoint fragments

Historically fragments have resulted from partitioning the supersystem, i.e., each nucleus appears in one, and only one, fragment. More recently methods which rely on non-disjoint fragments have been developed too. The Fragmenting component should avoid assuming that fragments are disjoint.

- general use

As motivated above, a number of methods require fragmenting a

ChemicalSystemobject. The Fragmenting component should avoid assuming a particular method of fragmentation strategy.

Out of Scope

- n-mers

A lot of (generalized) many-body expansion methods distinguish between fragments and unions of fragments (an “n-mer” being the union of n fragments). In practice, if one views a set of n-mers as set of non-disjoint fragments, the “n-mer” distinction becomes somewhat immaterial. Thus, because of the non-disjoint fragments consideration we feel that the Fragmenting component does not need to distinguish between fragments and n-mers.

- Expansion coefficients.

Usually the properties of the fragments are combined as a linear combination. The weights of this linear expansion will be stored elsewhere. Part of the motivation for not including the weights here is that in many cases the weights depend on more than just the fragment/field, e.g., they may also depend on the AO basis set (think basis set superposition error corrections) and/or level of theory (think QM/MM or other multi-layered theories).

Fragmenting API

Most fragmentation workflows start with an already created ChemicalSystem

class and then fragment that. Below is the proposed workflow and APIs for

fragmenting a ChemicalSystem.

// Opaquely creates the system to fragment

ChemicalSystem sys = get_chemical_system();

// Step 1. We start by assigning nuclei to fragments.

// This will be the sets of nuclei in each fragment

FragmentedNuclei frag_nuclei(sys.molecule().nuclei());

// Usually assigning nuclei to fragments is much more complicated than this

// but for illustrative purposes we just make each fragment a single nucleus

for(auto i = 0; i < mol.nuclei().size(); ++i){

frag_nuclei.insert({i});

}

// Step 2. In many cases fragmenting will break covalent bonds and we will

// need to cap the nuclei.

// For demonstrative purposes we assume that there was only a bond between

// nuclei 0 and 1 that needs capped

frag_nuclei.add_cap(0, 1, Nucleus{...}); // Cap attached to 0, replacing 1

frag_nuclei.add_cap(1, 0, Nucleus{...}); // Cap attached to 1, replacing 0

// Step 3. Need to assign electrons to the fragments

// This will hold the "Molecule" piece of each fragment

FragmentedMolecule frag_mol(sys.molecule());

for(NucleiView frag_i : frag_nuclei){

// Adds nuclei (and caps) and declares it as a neutral singlet

frag_mol.insert(frag_i, 0, 1);

}

// Step 4. Assign fields to each fragment

// This will hold the final fragments (which are each a ChemicalSystem)

FragmentedChemicalSystem frag_sys(sys);

for(MoleculeView frag_i : frag_mol){

// Adds molecule and its external field

frag_sys.insert(frag_i, ...);

}

Fragmenting Design

The chemical system hierarchy consideration means that our architecture will need to mirror the chemical system hierarchy. There’s at least two ways to do this:

FragmentedNuclei,FragmentedMolecule, etc. orFragmented<Nuclei>,Fragmented<Molecule>, etc.

Which brings us to the question “To template or not to template?”

A class template like Fragmented<T> works best if the same definition works

for most valid choices of T. If however Fragmented<T> would need to be

specialized for most valid choices of T there is little to gain over the

non-templated option. To this end we note the types differ in that:

Fragmented

Nucleimust worry about caps.Fragmented

Moleculemust worry about the electrons per fragment.Fragmented

ChemicalSystemmust worry about the fields per fragment.

That said there’s also common aspects like:

Fragmented<T>objects all storeTobjects.Fragmented<T>is container-like (i.e., needsat,size, etc.)

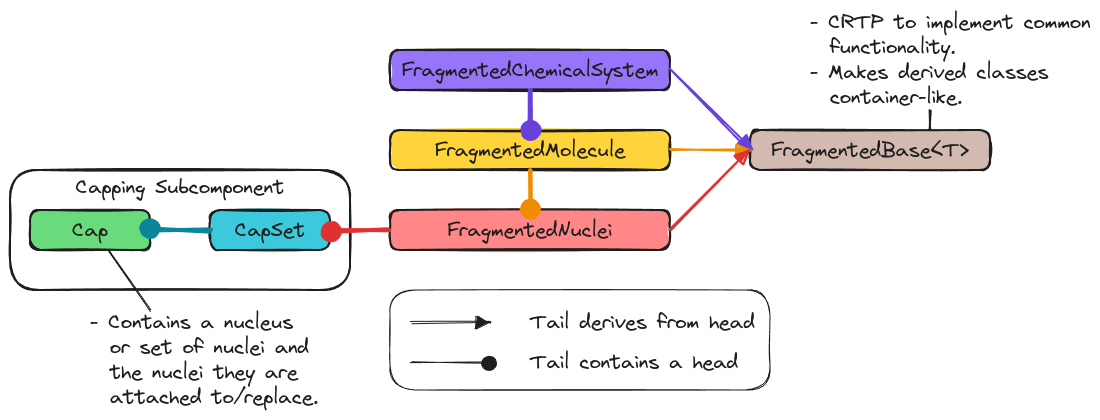

Fig. 8 Architecture summary of the Fragmenting component of Chemist.

Ultimately we have opted for the architecture shown in Fig. 8. The major pieces are summarized below.

FragmentedBase Class

Full discussion: Designing the FragmentedBase Class

As we briefly touched on when debating whether to have a class template or not,

the containers of FragmentedNuclei, FragmentedMolecule, and

FragmentedChemicalSystem have some common functionality, like accessing the

superset. The FragmentedBase<T> class template is introduced to factor out

common functionality. Here the template type parameter T is the class which

derives from FragmentedBase<T> and is used to implement

FragmentedBase<T> via the curiously recurring template pattern (CRTP). The

use of CRTP makes slicing unlikely.

FragmentedNuclei Class

Full discussion: Designing the FragmentedNuclei Class.

Stemming from chemical system hierarchy we know we will have to

fragment each piece of the ChemicalSystem hierarchy. The most fundamental

piece is the Nuclei part of the ChemicalSystem class and the

FragmentedNuclei class is charged with representing a fragmented

Nuclei object. The FragmentedNuclei object determines whether the

fragments are disjoint or not. This is done based on whether or not any given

nucleus appears in more than one fragment. If a system contains caps, the nuclei

for those caps live in the FragmentedNuclei object.

FragmentedMolecule Class

Full discussion: Designing the FragmentedMolecule Class.

The FragmentedMolecule class is responsible for holding fragments taken

from a Molecule object. It is composed of a FragmentedNuclei object, the

charges of each fragment, and the multiplicities of each fragment.

FragmentedChemicalSystem Class

Full discussion: Designing the FragmentedChemicalSystem Class.

The FragmentedChemicalSystem class is designed to hold fragments taken from

a ChemicalSystem object. At present this simply entails holding a

FragmentedMolecule object, but will eventually include holding the fields

for each fragment as well.

Capping Component

Full discussion: Capping Design.

The last key piece of the Fragmenting component is the capping subcomponent

and its major classes: Cap and CapSet. Capping is introduced in response

to the caps consideration. The use of a separate CapSet class, as

opposed to just adding the caps to a Nuclei object, facilitates telling the

caps from the “real” nuclei. Furthermore the caps have additional state beyond

that of a nucleus (or set of nuclei) including what nuclei they replace and what

nuclei they are attached to.

Summary

- chemical system class

Fragmenting a

ChemicalSystemresults in a container-like object of typeFragmentedChemicalSystem, the elements of the resulting object are the fragments of the supersystem. Fragments are implicitly convertible toChemicalSystemreferences in order to leverage existing algorithms.- chemical system hierarchy

This consideration is essentially a generalization of chemical system class and is addressed by

FragmentedNuclei,FragmentedMolecule, andFragmentedChemicalSystem. Each of which maps to a respective class in theChemicalSystemclass hierarchy.- caps

The capping component is charged with representing the caps. The nuclei for the caps are added to the system in the

FragmentedNucleiobject. The electrons are added in theFragmentedMoleculeobject.- non-disjoint fragments

This consideration is ultimately a design consideration of the

FragmentedNucleiclass.- general use

The Fragmenting component is largely made up of a container-like object and objects supporting that container. The classes use generic language which is widely applicable across scenarios.

Additional Notes

This design discussion was started as part of Chemist PR#361.