Cache Design

As a consequence of our Memoization Design strategy we have decided to implement an associative container, called “the cache”, to address the remaining memoization considerations. As was briefly noted in the memoization section, and explicitly called out in Checkpoint/Restart checkpoint/restart (C/R) will also be handled by the cache.

Note

We use the convention that “cache” or “the cache” refers to the concept and

that Cache refers to the class.

Cache Considerations

The considerations for the cache are really the union of the memoization considerations not considered in the Memoization Design section with the union of the checkpoint/restart (C/R) considerations not considered in Checkpoint/Restart. The memoization considerations focus on using the cache to avoid recomputing quantities, whereas the C/R considerations focus on how we should save the cache so that it can be reloaded and resued at a later time.

In the Memoization Design section it was decided that at the core of the cache is a high-performance associative array. The remainder of this section focuses on enumerating considerations pertaining to how one can unify the considerations in the Memoization Design section with the associative array concept.

Since memoization occurs per type

T(Tderived fromModuleBase) the actual cache will be a nested associative array (Tmaps to an associative arrayAandAactually maps the inputs to results)Will likely want to compress values and/or dump them to disk

What are the keys? Input values? Hashes? Universally Unique IDs (UUIDs)?

How many entries do we expect in a module’s cache? 10s? 100s? 1000s?

Cache entries are ultimately calls to a module. In a given run, a module probably gets called less than 10 times, maybe in the 100s for an iterative process, or a very fundamental and frequently called module.

1000+ calls is not unfathomable, but probably rare enough to justify treating it separately

There’s a number of associative array types; which one(s) do we want?

Certain structures excel at determining if an entry exists. Others excel at being able to add entries.

Checksums for data validity?

Needs to operate in a distributed environment

Each process gets its own cache?

For traditional memoization, distributed objects will stay distributed

For C/R less clear

Could do a checkpoint per process

Could do a single, sycnhronized, checkpoint

Could do something in between

Cache Implementations

At its heart the cache involves associative arrays and conceptually we may be

able to use an existing high-performance C/C++ library to implement it. This

section explores the available options, their features, and ultimately their

suitability for our Cache class.

Note

The notes on these libraries are primarily based off of documentation. I do not have experience with any of the libraries so the descriptions may be inaccurate. Activity, star, and watcher information was accurate as of March 2022 and may have changed since then.

C++ Associative Container Libraries

First up are the C++ libraries on GitHub with the associative-array tag:

HArray

Uses a trie (instead of hash table or binary tree)

Prefix compression

Save/load to disk

GPLv3

Appears to be abandoned (last commit July 2021). 88 stars and 12 watchers.

AVL Array

Fixed size array (designed for embedded systems)

MIT License

Appears abandoned (last commit March 2020). 28 stars and 4 watchers.

uCDB

Designed for Arduino (apparently a competior of Raspberry Pi)

Seems like it can only read from existing databases

Not licensed.

Active development. 5 stars and 1 watcher.

Vista

Implements various span classes (including an associative array one)

Operate on existing contiguous memory.

Does not appear to allow modification.

No license.

Likely abandoned (last commit May 2020). 4 stars and 3 watchers.

ceres

It looks like it’s an example project.

Appears to just wrap

std::mapGPLv3

Likely abandoned (last commit April 2021). 0 star and 1 watcher.

C Libraries for Assoicative Containers

Next are C libraries on GitHub with the associative-array tag:

libdict

Looks like it’s just implementations of common data structures with C APIs (no special features)

BSD

Likely abandoned (last commit May 2019). 255 stars and 28 watchers.

thmap

Concurrent implementation of a trie-hash map

BSD

Likely abandoned (last commit April 2020). 63 stars and 7 watchers.

rhashmap

Hash map that uses robin hood hashing

BSD

Last commit September 2021. 40 stars and 5 watchers.

cdict

Seems like a limited functionality replacement for std::map (in C)

MIT

Last commit November 2021. 2 stars and 1 watcher.

core-array

Appears to be a simple map class which can only have integer keys and integer values.

AGPLv3

Last commit September 2021. 1 star and 1 watcher.

c_vector_map

Maps strings to integers.

Documentation says it was designed/optimized for a highly-specific usecase.

BSD

Last commit April 2021. 0 star and 1 watcher.

Data-Structures-C

Appears to be someone’s toy project to learn about data structures.

Documentation states it’s not production ready

DO_WHATEVER_YOU_WANT license

Likely abandoned (last commit July 2019). 0 stars and 0 watchers.

Databases

While we’ve focused on associative arrays up to this point, what we’re after can also be considered a database. The advantage of moving to databases is that we get some real heavy-hitters contributing software. Putting the cart before the horse, our current cacheing strategy will rely on databases for a number of the considerations. The full design discussion is lengthy and we defer that conversation to Database Design.

Cache Strategy

Ultimately a lot of the Cache’s implementation will get punted to an underlying

class Database. The design of that class, and how it addresses the Cache

considerations is beyond our current scope, but can be found

here. This discussion focuses on the design of the API

wrapping the Database class.

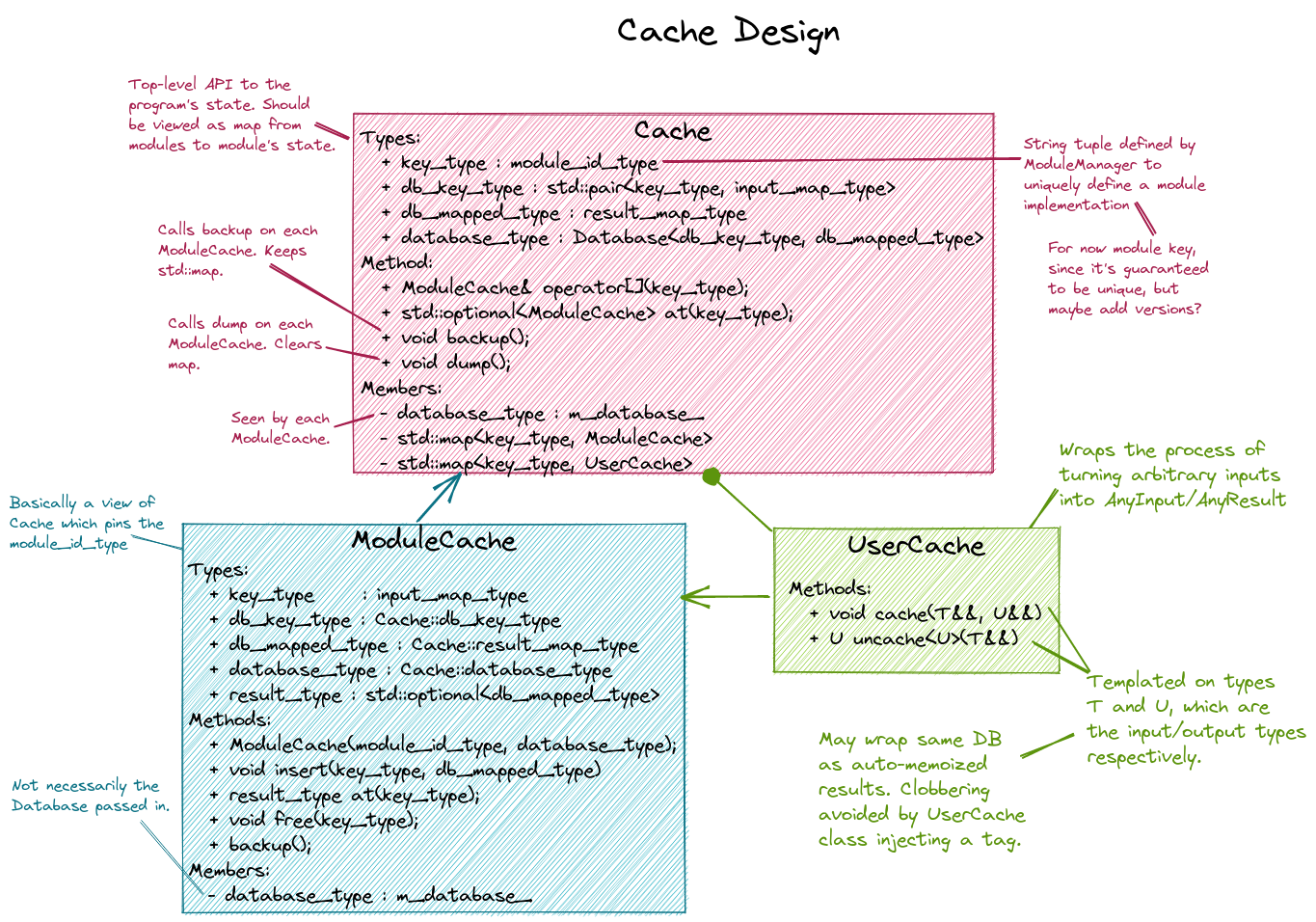

Fig. 10 Main design points of the Cache and ModuleCache classes.

Fig. 10 summarizes the design of the Cache class. Each

ModuleManager instance can have at most one Cache instance. This

ensures there’s a single source of truth for the program. The Cache will be

hierarchical since memoization only makes sense for modules of the same C++

type. The Cache refers to the entire cache object, whereas ModuleCache

refers to the cache for all modules of the same C++ type. Thus Cache can

be thought of as a map from C++ type to ModuleCache instances. In lieu of

the actual C++ module type, we define a concept called the module ID. For now

the Module ID is simply the module key that a module was originally registered

under, but in the future may be expanded to include for example version

information. Each ModuleCache is thought of as a map from a set of inputs to

a set of results.

Under the hood of ModuleCache we use the Database class to store the

actual data. From the user’s perspective the Database class implements the

Cache class and ModuleCache instances are slices of the Database. We

accomplish this by having the keys of the database be pairs whose first element

is the module ID and the second element is the input set (values in the database

are the result sets). Database is implemented by a polymorphic PIMPL.

Additional PIMPLs can be added to cover different database backends and/or

nested for more comlicated C/R scenarios.

It is worth noting that in this design the Cache class is very similar to

the Database class and could at this stage just be a Database; however,

we maintain separate classes because Cache is the public API and

Database will be an implementation detail.

So far this strategy does not address how iterative modules will be memoized

yet, nor will the database help on this issue. The primary problem to solve is

how to avoid needing to store all of the intermediate results. Our current

strategy is to more or less punt and make module developers do it. More

specifically the Cache class will maintain a second module to

ModuleCache mapping (these ModuleCache instances will actually be held

as instances of the derived UserCache class). Module developers are

able to access the UserCache through the ModuleBase class and are free

to cache/uncache whatever values they want.

The use of the UserCache with iterative modules has a potential pitfall. In

general the UserCache will wrap the same Database as the ModuleCache

(this facilitates using a single C/R backend). Furthermore, a lot of times the

inputs to the iterative module are the same as the inputs used to tag

intermediate results (and the intermediate results are often the same type as

the module’s results). In turn restarting an iterative module that has not

converged may lead to the iterative module being memoized to the last

intermediate even though it has not converged. To prevent this, UserCache

tags its entries before dumping them, whereas ModuleCache does not.

When attempting to memoize an iterative module, tagged cache entries will not be

considered. If no untagged enteries are found control goes into the module.

Inside the module, the user checks the UserCache instance (which in turn

only considers tagged entries) and the module is able to restart using the last

intermediate.

Cache Considerations Addressed

With respect to the cache considerations this strategy addresses the following considerations:

Each class

Tderiving fromModuleBaseis assumed to wrap a unique algorithm. When memoizing it thus only makes sense to consider results computed by otherTinstances.Addressed by

CachevsModuleCache

Failing to memoize when appropriate will affect performance

There’s only so much we can do here. Ultimately it’s up to the database backend to determine if a set of inputs has been seen or not. Concievably, the database could use special comparisons to determine if two objects are equal.

Memoizing when not appropriate will compromise the integrity of the scientific answer.

Again this is up to the database backend. In our initial design two objects must compare value equal to be considered the same. If value equality is implemented correctly there is no reason why false memoization will occur.

Memoizing iterative (recursive) function requires special considerations

Addressed by having

UserCache

Comparing objects can be expensive (think about distributed tensors)

It’s our opinion that optimizing value comparison is easier than trying to implement a general comparison solution based on hashing or the like. Object developers are of course free to use hashing inside their object’s value comparisons as an optimization.

Module developers may want to do their own C/R.

Addresed by having a

UserCache. Module developers can put whatever they want in that cache and have it be checkpointed.Module developers are also free to ignore the

UserCacheand do something else if they would like.

Since memoization occurs per type

T(Tderived fromModuleBase) the actual cache will be a nested associative array (Tmaps to an associative arrayAandAactually maps the inputs to results)The

CacheandModuleCacheclasses addresses this.

What are the keys? Input values? Hashes? Universally Unique IDs (UUIDs)?

From the perspective of the

Cachethe keys are input values. TheDatabaseimplementation is free to map the input values to proxy objects such as UUIDs if it so likes.

How many entries do we expect in a module’s cache? 10s? 100s? 1000s?

Cache entries are ultimately calls to a module. In a given run, a module probably gets called less than 10 times, maybe in the 100s for an iterative process, or a very fundamental and frequently called module.

1000+ calls is not unfathomable, but probably rare enough to justify treating it separately