Designing the Call Graph Component

Stemming from the discussions in Architecture of PluginPlay and Designing the Module Manager PluginPlay needs a call graph component. This section describes the overall design of that component.

What is a call graph?

Note

To make contact with typical computer science terminology the use of static and dynamic call graphs differ somewhat in this section than in other places of the manual.

Call graphs are graphs (in the mathematical sense) that represent the control flow of a program. Each node in a call graph represents one function in the program. Edges between nodes are directed from the calling function to the called function. Given the complexity of most programs, call graph representations are typically determined by running the program and recording the control flow. The resulting call graph is only representative of the run used to generate it. Such call graphs are typically known as “dynamic” call graphs, since they are generated dynamically. In theory, there also exists a “static” call graph which shows all possible control flow paths through the program; however, for most programs this call graph is far too complicated to be useful and determining it has undecidable complexity.

In the PluginPlay call graph component we define “call graph” slightly differently than the computer science definition just given. In particular, in PluginPlay’s call graph component, the nodes are user-provided Module objects, not individual function calls. Similarly, the edges go from the calling Module object to the callee Module object, not between individual function calls. The net result is that PluginPlay’s call graph component is a coarse-grained representation of the actual call graph.

Call Graph Considerations

Sections Architecture of PluginPlay and Designing the Module Manager passed a number of considerations to the call graph component which we list here:

Inspect and modify the call graph

Need to be able to add/remove nodes at runtime

Must be able to “rewire” the call graph

Leverage cache component for memoization, saving/loading, and checkpoint/restart

Dynamically determine interface for calling a module

Modules may be callable in different ways, similar to overloads in C++

Remain domain agnostic

Need to be compatible with a domain’s native types

Realize that the set of types in a domain may expand over time

Avoid directly coupling one domain to another

Support a Python API

Using pure Python, there is no way to instantiate a class template (or function template) at runtime, meaning all interfaces must be known at compile time. N.B., Cppyy 24 is a notable exception.

Call Graph Design

Note

PluginPlay was designed before considering Cppyy and this discussion assumes that only pure Python bindings are being considered.

Node Design

As established the nodes of the call graph will be PluginPlay Module

objects and will need to be function-like. We propose the Module class to

describe the modules. Users will create Module instances which contain

their algorithms and any state the algorithm needs. Then the Module object

can be run by providing it any inputs it needs. We do not want to use the

constructor for running the module, as the constructor is more naturally used

to initialize any state the Module may have. Thus we require the Module

class to have a run method. The run method will take a series of inputs

and return zero or more results. Since the run method will be written in

C++ we now have to decide on the types of the inputs/results. The consideration

to remain domain agnostic immediately suggests a templated solution and we

suggest that run looks like:

template<typename...Results, typename...Inputs>

std::tuple<Results...> run(Inputs&&...);

While a perfectly acceptable C++ solution, this API can not be exposed

to Python without instantiating every possible function template, i.e., to

expose this to Python we need to know every possible choice for the Results

and Inputs parameter packs. In turn, PluginPlay would need to either know

domain information (which we don’t want it to know) or we would have to

restrict the allowable types to some set (which could have serious performance

consequences).

A common C++ technique for passing arbitrary types, in a non-templated type-safe

manner is “type erasure.”. For now we ignore the details of how type erasure

works and simply note that it requires us to define a class to act as, more or

less, a common base class for every type we may want to wrap. We thus establish

the AnyField class for type erasing inputs/results. We also note that

templating is only required to create the AnyField object and to unwrap it,

the actual class is not templated. In terms of AnyField we can write the

run API as:

std::vector<AnyField> run(std::vector<AnyField> inputs);

Where we switched to std::vector to avoid needing to know the number of

fields at compile time.

Note

Python actually uses a similar trick to interface with the C code underlying

it. By ensuring that we can convert AnyField objects to/from Python

handles, we are able to expose this interface to Python seamlessly. Modules

written in Python get inputs that are Python objects and the returned

Python objects are automatically converted to AnyField objects.

Similarly, when an AnyField object containing a Python object is

unwrapped in C++ we know the C++ type we want and under the hood we simply

cast the Python object to that type before returning it to the C++.

We could stop here, but actually using the run members is quite clunky. The

problem is that at compile time every module is now interchangeable with every

other module because they all have literally the same API. However,

type erasure is still type-safe, it just defers the type check to runtime.

Thus it should be noted that at runtime they are NOT all compatible. This

is because inside the run function you’ll have to do something like:

std::vector<AnyField> run(std::vector<AnyField> inputs){

// Our function expects two arguments

assert(inputs.size() == 2);

// Argument 0 should be of type T

T arg0 = inputs[0].unwrap<T>();

// Argument 1 should be a double

double arg1 = inputs[1].unwrap<double>();

// Rest of function...

}

While this will always compile, it will raise runtime errors if the number of

inputs is not two, the first argument is convertible to type T, or if the

second argument is not convertible to a double. Having to wait until

runtime (and possibly very far into a session) to find out if the call graph

is wired correctly is undesirable.

Another problem is say that we have two modules whose run APIs essentially

are:

double run(double);

after we unwrap the AnyField objects. These modules are API

compatible at both compile time and run time. The problem is these modules may

do very different things despite having the same API.

To address the problems of: runtime type-checking and discerning callbacks we introduce the “Property Type” component. The name “property type” comes from the fact that most of the original use cases focused on using property types to discern among modules which compute different properties, but have the same API. PluginPlay only includes infrastructure for registering property types, not the actual property types. This is because property types are necessarily domain-specific and should be defined downstream of PluginPlay.

Each Module internally must set the property types that it satisfies.

By stating that a module M satisfies property type A the module

developer of M is saying that anytime anyone needs a module capable of

computing A, they may use M. In this sense, PluginPlay uses each

Property Type as a Strong Type, helping avoid accidentally using

a module in the wrong place. To address the runtime type-checking problem

each property type also includes the types of the inputs and the results.

Data Flow in to/out of a Module

The previous sections introduced the components of the call graph. With these pieces it is now possible to describe how nodes will actually call one another.

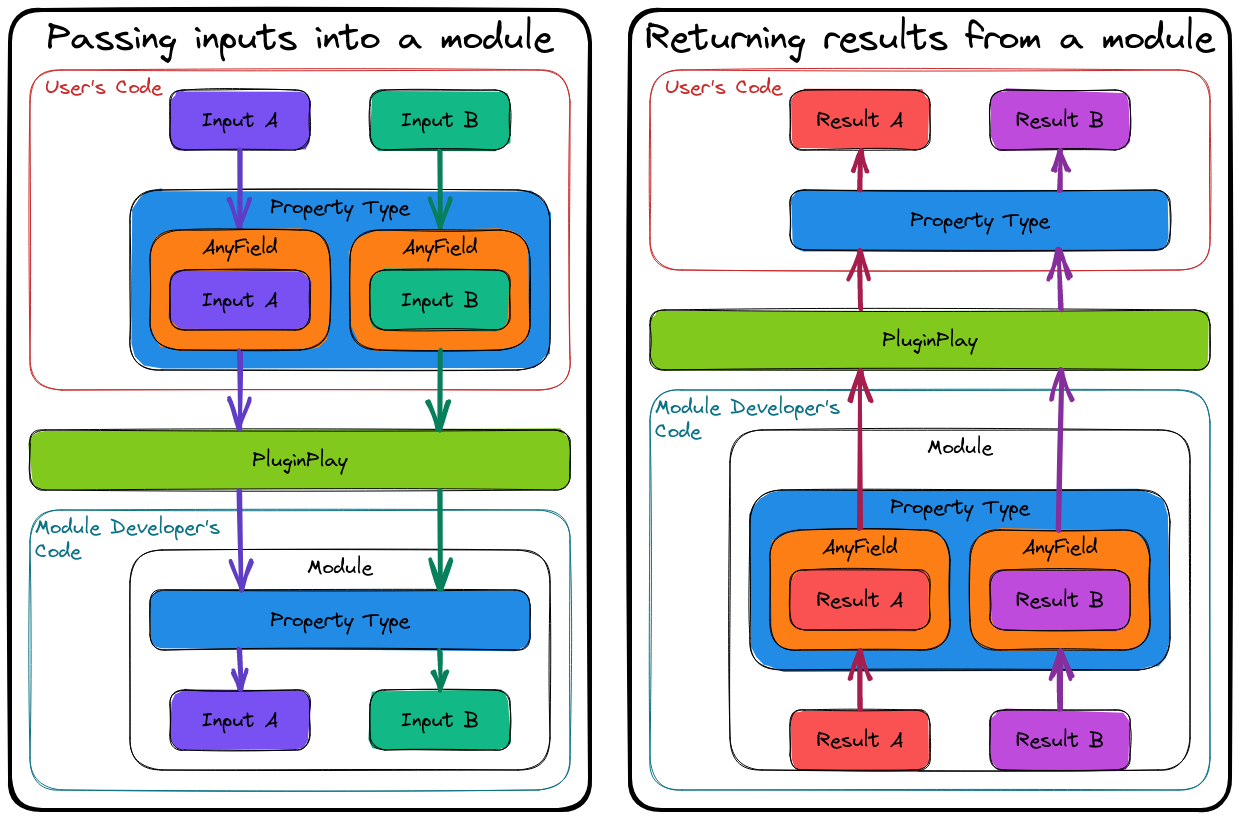

Fig. 13 Left how typed information traverses the user’s code into the module developer’s code and right how typed information leaves the module developer’s code and enters the user’s code. Note that all data traverses the code boundary in type-erased form.

To try and make the design from the last section more intuitive consider

Fig. 13. The left side shows the process of passing data

into a Module. This can be passing data into the first Module in

the call graph or from one Module in the call graph to another. The

first step is to type-erase the data. This is done by feeding the data through

the Property Type resulting in AnyField objects. The AnyField

objects then cross the code boundary into PluginPlay, where cacheing and

memoization may occur, before being forwarded to the Module. Inside the

Module the same Property Type is used to unpack the AnyField

objects. Returning data simply reverses the process.

There are several points to note about this design:

User and module developers need to agree on a set of property types. This simply amounts to standardization, i.e., the field has to agree on what it means to compute a specific property, including the classes.

N.B. with good class design it is possible to avoid coupling the identity of the class to the data layout of the class, e.g., by using PIMPL.

The user code never directly touches the module developer’s code, nor does the module developer’s code every directly touch the user’s code.

This places onus on PluginPlay to maintain its APIs, but avoids the user and module developer’s codes from every having to know about one another.

This facilitates extending the call graph later since new code only needs to know about PluginPlay (and the property types)

Type-erasure is NOT serialization

Serialization often has a large performance-penalty

Type-erasure is a pointer cast and extremely cheap on the scale of most scientific simulations.

Assembling the Call Graph

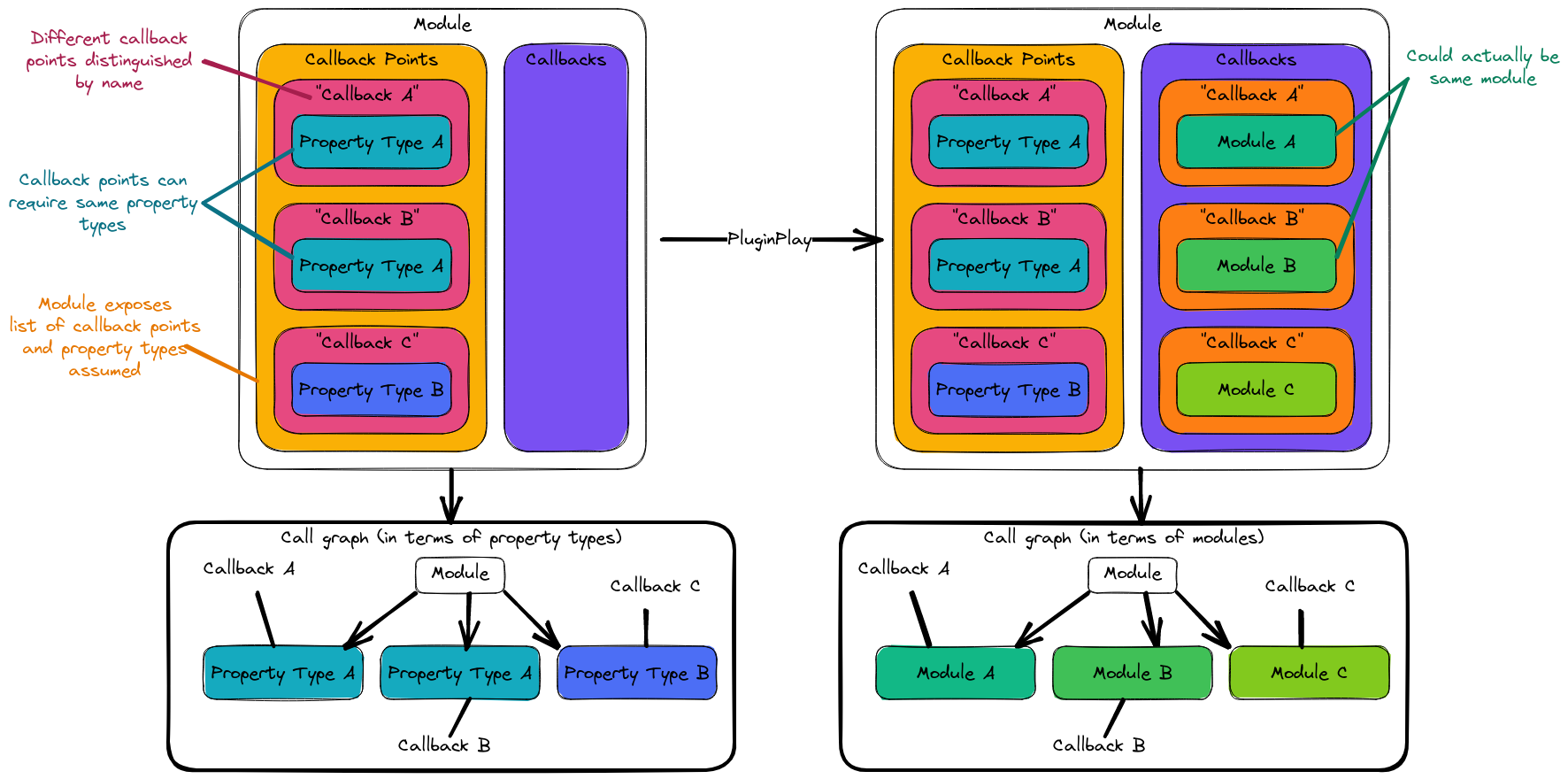

With a design in place to wrap algorithms in modules, and a design for how to call the modules, the last piece of the call graph component is literally assembling the call graph. As a first pass we have adopted a simple solution depicted in Fig. 14.

Fig. 14 Each module must register with PluginPlay the number of callback points it exposes, and the property types which will be used at those points. PluginPlay chooses (with a lot of help from the user) the modules for each callback point and gives them to the module at run time.

Rather than create a literal call graph object to represent the call graph we

have taken a linked list approach. When a module developer writes a module they

register with PluginPlay all of their callback points. In

Fig. 14 the developer has registered three

callback points. To distinguish callback points within the module, each

callback point is assigned a unique name (unique within the scope of the

module). Here these names are "Callback A", etc.. In addition to the name

of the callback point, PluginPlay also needs to know what Property Type

will be used for the callback. Module developers register the domain-specific

property type they will use. As noted in Fig. 14

the property types need not be different. These steps are written as part of

developing the module (although they will actually get executed at run time).

When it comes time to assemble a call graph, PluginPlay will look at the first module to call, retrieve its list of callback points, and determine which module, from the module pool, will be called at which call back location. Once the callbacks are determined, the module is linked to them and the process is repeated recursively inside each callback module.

Summary

The current design addresses the above considerations by:

Inspect and modify the call graph

The call graph is made up of components which have run time state.

Run time state of call graph can be inspected and modified

Able to swap modules out.

Leverage cache component for memoization, saving/loading, and checkpoint/restart

PluginPlay is invoked before and after each module call.

This allows PluginPlay to do cacheing, memoization, and saving.

Memoization falls to the module component.

Dynamically determine interface for calling a module

All modules have the same, type-erased base API.

It is up to the user and module developer to determine the property type to use. While the list of property types can not evolve at run time, it is possible to use logic to determine which property type to use at runtime.

Remain domain agnostic

Type-erasure preserves the domain’s native types, but uses pointer trickery to avoid exposing them.

Type-erasure only needs to know type of object at creation and unwrapping so more types can be wrapped later

All calls go through PluginPlay, which avoids directly coupling domains

Support a Python API

PluginPlay exposes type-erased APIs which can easily interoperate with Python’s object handles and duck typing

Python object handles can be cast to C++ types under the hood of the type-erased objects

This design has also mandated the creation of several components and design criteria for those components.

Module Component

Users of PluginPlay write algorithms in

ModuleobjectsModuleconstructor is reserved for initializationModulemust exposerunmember for running the object given a set of type-erased inputs, and must return a set of type-erased outputsStore a list of callback points, and a list of callbacks for those points

Any Component

AnyFieldclass for type-erasing inputs and results to modulesNeed to be compatible with Python object handles

Property Type Component

Used to restore compile time type checks

Facilitates wrapping/unwrapping type-erased objects

Establishes domain-specific properties a module can compute

Downstream users register property types

PluginPlay infrastructure must be agnostic to API codified by property type,

Additional Notes

For simplicity we assumed that each module object stores a list of the modules it will call, and PluginPlay manipulates this list. We could create a full fledged graph object at a later point. This would facilitate searching the graph.